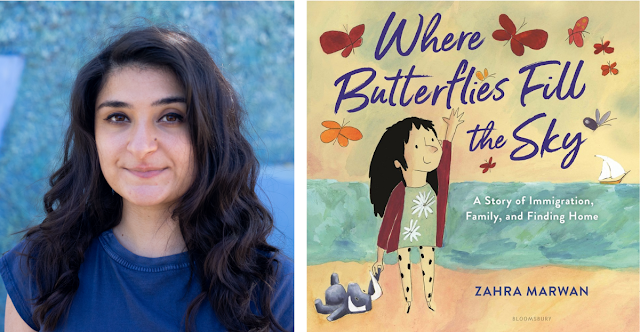

Although I’ve been very comfortable by the oddity that is my life, I realized as the years went by that I often have to explain who I am to most strangers I meet.

“I’m Kuwaiti, but I grew up in New Mexico.

I love my culture and home, I just never had the right to live there.

Yes, I was born there. My mom is Kuwaiti. My dad should have been Kuwaiti.”

And then I start talking about the 1930’s in the Arab Gulf as if that’s normal small talk.

Statelessness is not a widespread or well-known issue, and gratefully neither is gender discrimination in regards to passing on citizenship in the West. All this to say, I remember the comfort of being in a place that my family was from. Where I looked like most people and had a large family and communal ties. And I remember the feeling of having to leave everything I loved and not knowing why. I was a child when I experienced the impact of displacement. And I was a child impacted by one of the many bureaucracies in this world that doesn’t work for people, but rather abstract ideals.

It is deeply personal. I remember so many details from my childhood. I had such a happy childhood. A million cousins I would play with every week at my grandfathers house. Older brothers who filled my head with stories and inspiration. And parents who loved me so much. I even have two memories while being too young to speak. One of hoping my mom would give me some of a potato she was cooking (she did!) and a second of hoping my brother would pick me up when all of the kids started playing tag around me (he did!).

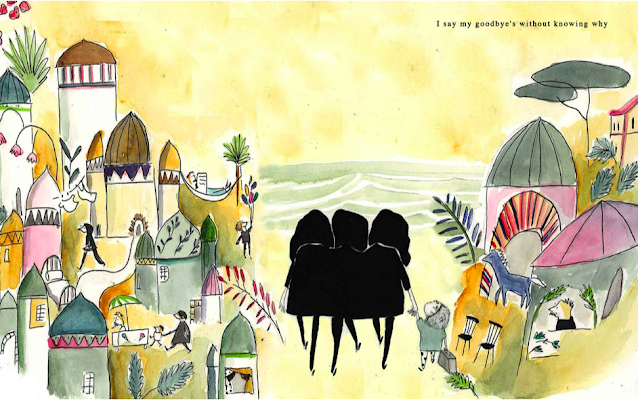

I didn’t want to leave my home as a child. And I remembered the confusing things adults were telling me. I didn’t know why I was saying goodbye, why things were shifting. I didn’t understand why no one spoke Arabic when we arrived to New Mexico, or when we were going to go back home.

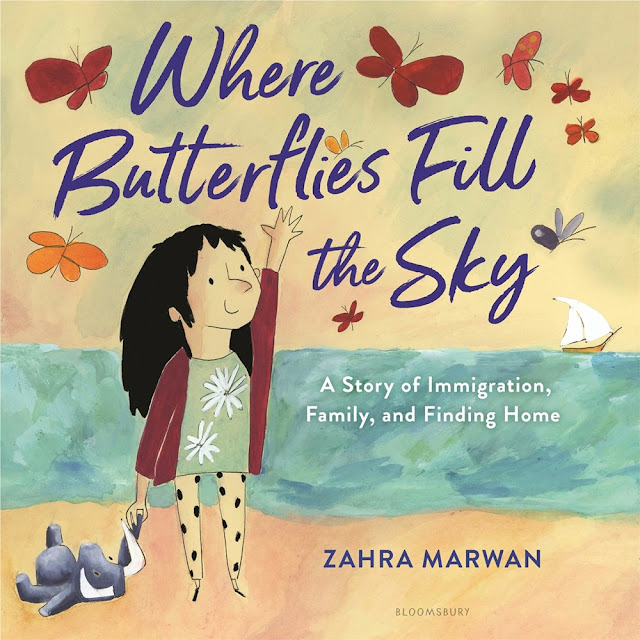

There have been times where I’ve wondered “is this a book for children?” I recounted it from how I felt as a child. The author’s note goes into detail about the open discrimination and arbitrariness of statelessness. A librarian said that these aren’t things children know, yet two stateless children as young as 10 committed suicide while I was working on the final art of this book at the prospect of a bleak future. There are children who are fully aware of what these suffocating policies are. Of how bureaucracies fail people.

LTPB: What did you find most rewarding in creating this book? What is the biggest lesson you’ve learned for your future projects?

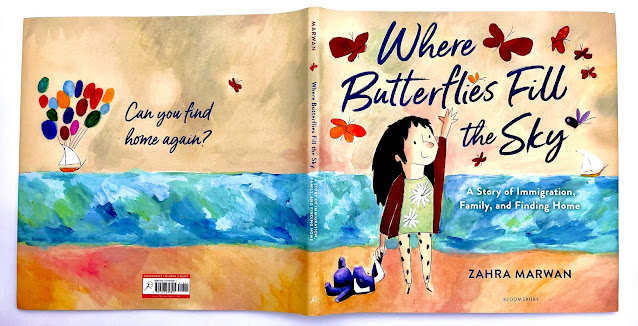

ZM: I found it to be really rewarding to see each phase of edits implemented into the art. How compositions and colors became more vibrant with each round. My editor Susan Dobinick was really instrumental in helping me compose the spreads, as well as helping the story flow. The Bloomsbury team was so patient and supportive as I made my way through the process for the first time. I wanted to make sure that I was honest in my renderings and experience. And I wanted this honesty to also reflect the two cultures in an objective way which was also whimsical and surreal.

I wanted to tap into cultural symbolism and flat compositions while pushing the narrative forward. I’ve learned for my future projects to work smaller and faster, to relax a little, and give myself space and time to build creatively. I also forgot while working on this book that my art and story will reach outside of my comfortable art communities in Albuquerque and Kuwait. That’s definitely something for me to keep in mind!

LTPB: What did you use to create the illustrations in this book? What can you tell us about your creative process?

ZM: I based a lot of the spreads in this book on illustrations I made in Kuwait in the Spring of 2019, where I spent three months. I often write and draw what is happening in my day to day life. I hadn’t spent this much time in Kuwait in years, but had to be home to help my mom recover after leaving the hospital. It was an emergency trip home, yet I was offered an art residency at the Sheikh Abdullah Al-Salem Cultural Center. I implemented a lot of the inspiration I was seeing into my illustrations, even though it was a rather dark time personally. I often sketch, refine my lines, then add watercolor washes. I’ve recently started using tinted boards instead of watercolor paper to make the white ink pop as much as the black.

I also used imagery based off of ancient art found in Kuwait or on Failaka, an island 10 miles off of the Kuwaiti shore. There are ancient Greek ruins there. And I used a bull found from the ancient Dilmun civilization which spanned Kuwait to Bahrain to implicate ancestors. Kuwait has such a long sea-faring culture, that even ancient Mesopotamian or Sumerian sculptures of deities featured fish. And more personally, my dad had worked for the National Fishing Company in Kuwait.

LTPB: What are you working on now? Anything you can show us?

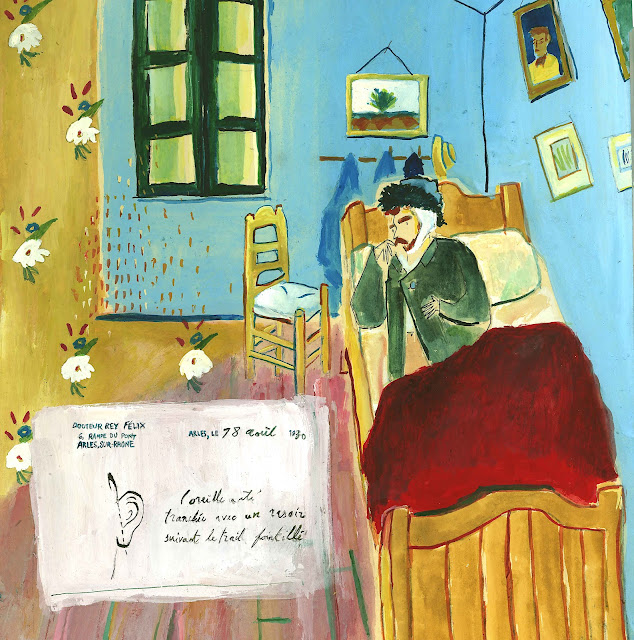

ZM: I’m working on a story with Feiwel & Friends about Van Gogh’s time in the Yellow House in Arles and the famous sunflowers he painted. I saw one of his paintings at the Milwaukee Art Museum during a short trip before the pandemic started and the description mentioned that he spent months decorating and making paintings in anticipation of Gaugin’s arrival. It really moved me, this notion of preparing a space for a friend. The way we are alone thinking of others.

LTPB: This seems silly since you already wrote your autobiography, but if you got the chance to write another picture book autobiography and you could choose anyone else (dead or alive!) to illustrate it, who would it be, and why?

ZM: If I were to write a picture book of another autobiographical aspect of my life, I’d like to illustrate it again! Or imagine, Decur! I’m still shaken by the beauty of his use of color and shapes in his book When You Look Up.

March 22, 2022 at 10:31AM noreply@blogger.com (Mel Schuit)